RL Framework: The Problem

In this post, you’ll learn how to specify a real-world problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), so that it can be solved with reinforcement learning.

The Setting

Let’s kick things off with a simple example. Imagine you’re playing a video game where you’re navigating through a maze. At first, you might bump into walls or take wrong turns, but over time, you learn the layout, figure out where the traps are, and start making smarter moves to reach the end faster and with higher scores. This process of learning through experience, where every choice brings you closer to mastering the maze, is a lot like what we see in reinforcement learning (RL), but on a broader and more complex scale.

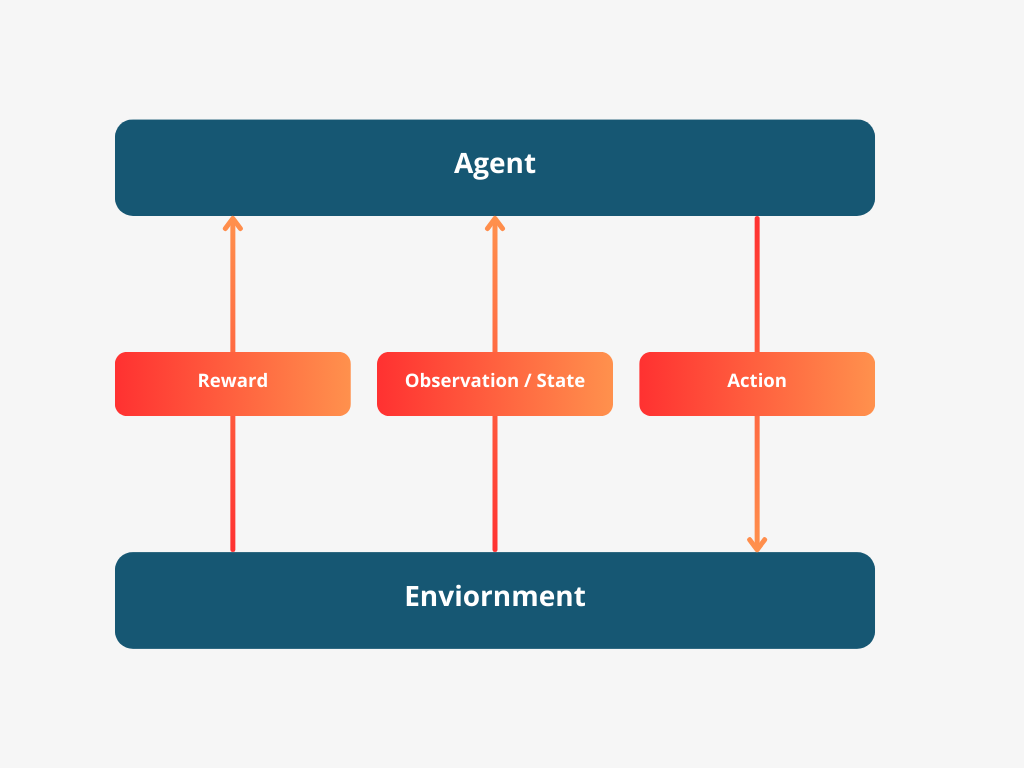

In RL, the concept is pretty straightforward: we have an agent, which could be anything from a robot to a software program, trying to figure out the best way to accomplish a task. The agent explores its environment, making decisions and learning from the outcomes of those decisions. The feedback comes in the form of rewards - positive for good decisions that move it closer to its goal, and negative for decisions that don’t.

Let’s break this down with a more relatable example. Consider a thermostat programmed to keep your home at a comfortable temperature. Initially, the thermostat might not know the best settings to use during different times of the day or in varying weather conditions. However, as it ’experiences’ how different settings affect the temperature and receives feedback (like adjustments made by the occupants), it learns and adjusts its actions to maintain the desired comfort level more efficiently.

The learning journey involves the agent interacting with its environment in a cycle of actions, observations, and feedback. The agent observes its current state (like the thermostat noting the current temperature), makes a decision (adjusting the temperature setting), and then receives feedback (the house reaching the desired temperature). This feedback is crucial because it tells the agent how well it’s doing and guides its future decisions.

In the context of RL, we often simplify the scenario by assuming the agent has a clear view of its environment’s state at each step. This helps us focus on understanding how the agent makes decisions and learns from them. We use terms such as ‘state’, ‘action’, and ‘reward’ to describe this process in a precise manner.

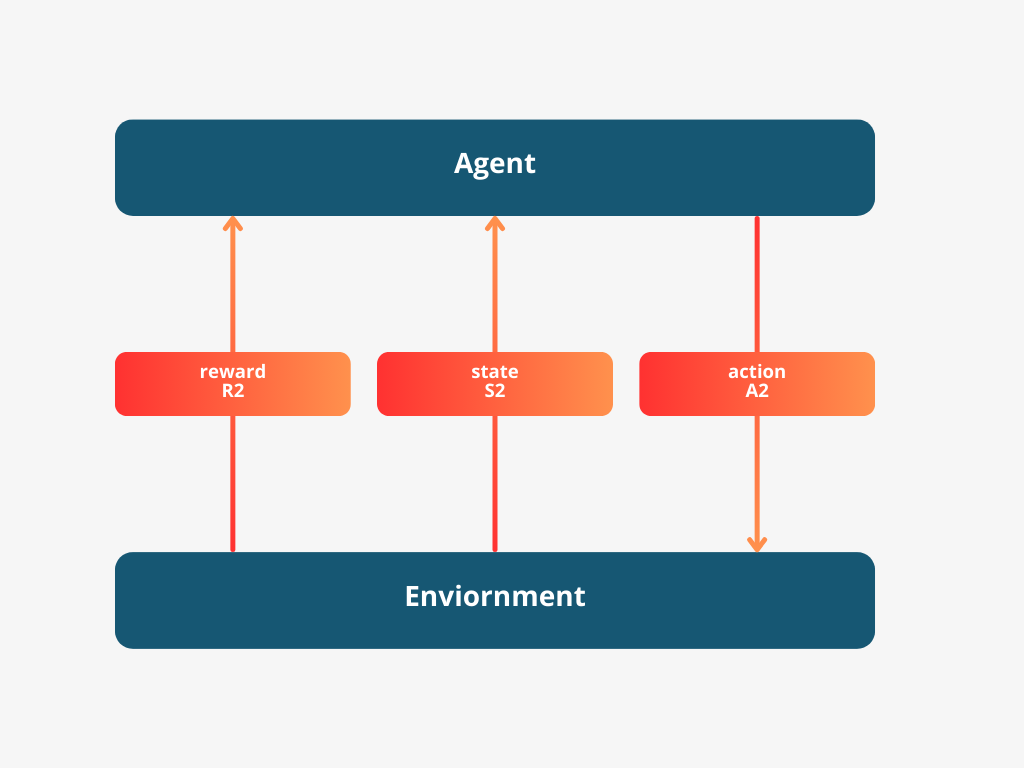

This is essentially reinforcement learning (RL), which doesn’t change much whether we’re talking about thermostat , self-driving cars, robots, or any other RL agents. Essentially, RL involves an agent (like our thermostat) figuring out how to act in its world. We look at time in steps and start with the agent seeing its world. From what it sees, the agent decides what to do next. After the action, it finds itself in a new situation and gets a reward, which tells it if the action was a good choice. This cycle of observing, acting, and getting rewards keeps going, with the agent always aiming to pick actions that bring the best rewards over time.

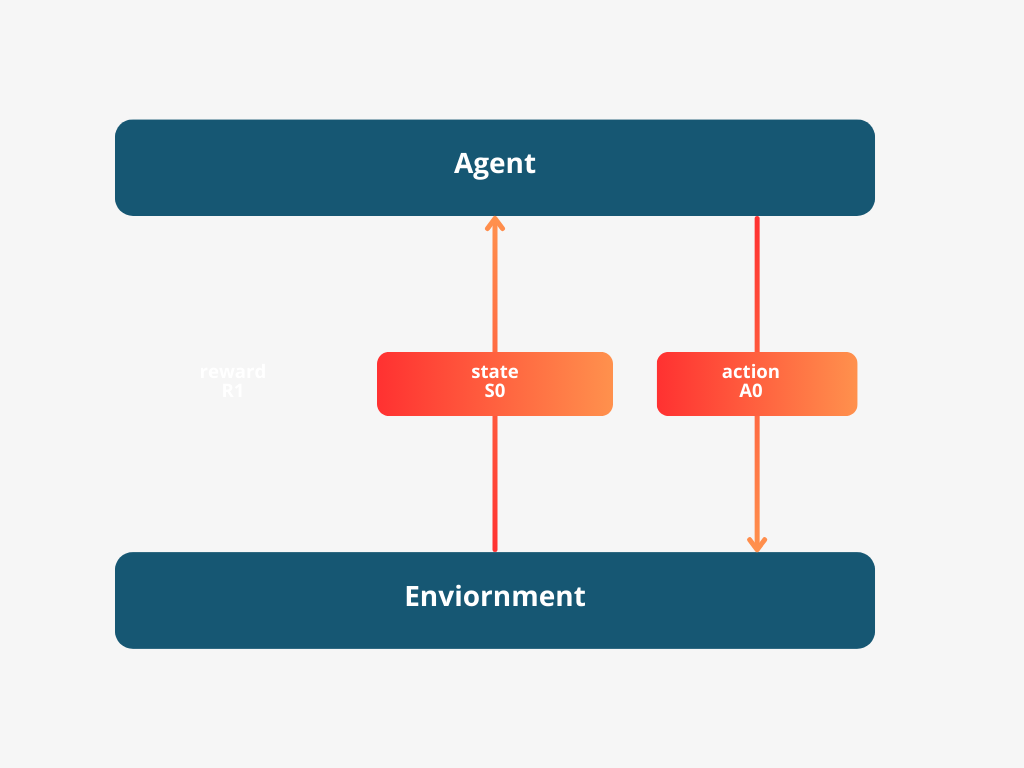

In simple terms, we often assume the agent can see everything it needs to make the best choices, although that’s not always true in real life. For our discussions, let’s stick with this idea because it makes the math easier. We’ll say the agent knows the state of its world at every step. Starting from step zero, the agent sees the world state (let’s call this $S_0$), chooses an action ($A_0$),

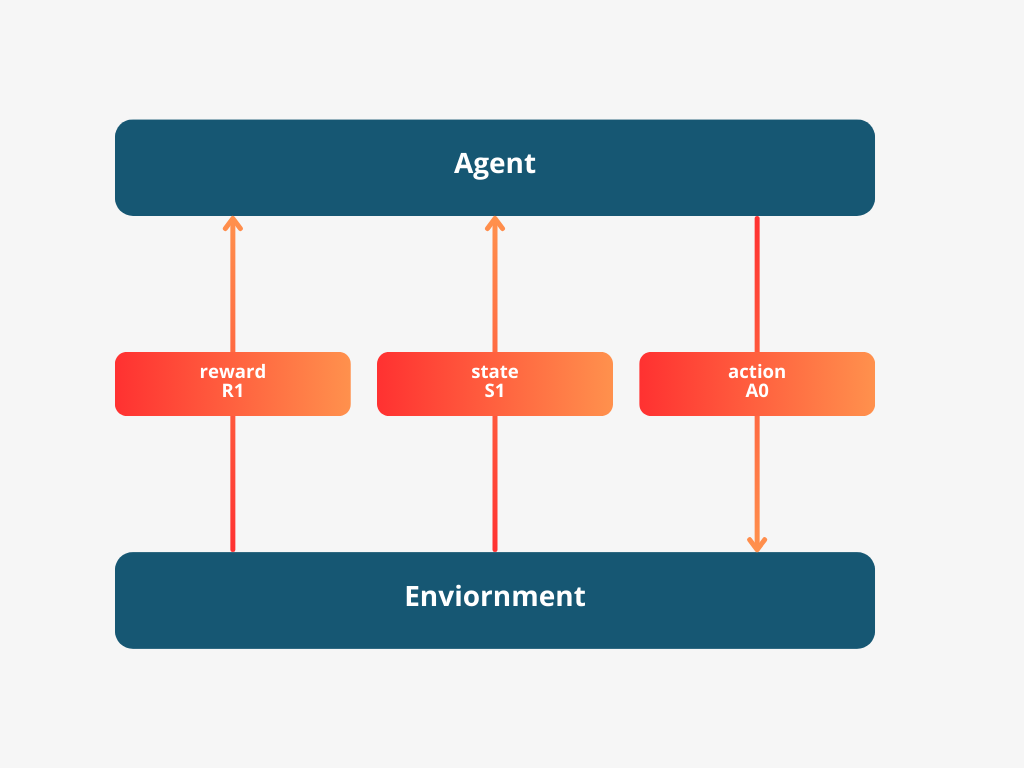

and based on that, the world changes to a new state ($S_1$), and the agent gets a reward ($R_1$).

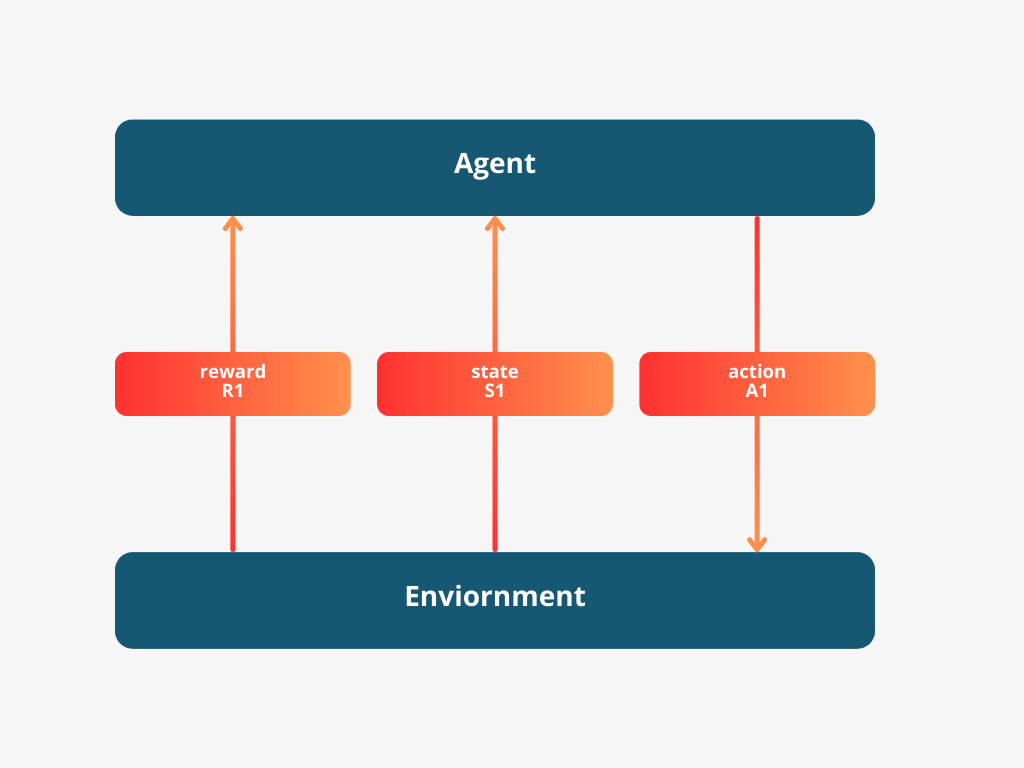

The agent then chooses an action, A1.

At timestep two, This process keeps repeating, with the agent continuously adjusting its actions based on the world’s state and the rewards it receives.

This interaction is manifest as a sequence of states, actions, and rewards.

$$ S_0, A_0, \underline{\mathbf{R_1}}, S_1, A_1, \underline{\mathbf{R_2}}, S_2, A_2, \underline{\mathbf{R_3}}, S_3, A_3, \underline{\mathbf{R_4}}, \ldots $$

Our goal in RL is for the agent to maximize its total rewards over time, which it can only do by interacting with its environment and learning from it. The agent has to follow the world’s rules, but by doing so, it learns which actions lead to the best outcomes. This is the core of what we’ll explore in this post. But remember, we’re applying mathematical models to real-world problems. If you’re thinking of solving a problem with RL, you’ll need to define the states, actions, and rewards, and figure out the rules of the world for your specific case. Throughout this post, we’ll explore various examples that show how to set up and solve problems using RL, giving you the tools and understanding you need to tackle challenges that can benefit from this kind of learning approach.

Episodic vs. Continuing Tasks

Let’s explore several real-world scenarios that conclude with a well-defined endpoint. For example, if we’re training an agent to play a game, the session ends once the agent either wins or loses. Similarly, if we’re conducting a simulation to train a car/robot to drive, the session concludes if the car/robot crashes. Not all tasks in reinforcement learning are like this; however, those that are, are termed episodic tasks. Here, an episode encompasses the entire sequence of interactions from start to finish.

In an episodic task within reinforcement learning, the interaction sequence can be represented as follows:

$$ S_0, A_0, R_1, S_1, A_1, \ldots, R_T, S_T $$

where:

- $( S_t )$ represents the state at time step $( t )$,

- $( A_t )$ represents the action taken at time step $( t )$,

- $( R_{t+1} )$ represents the reward received after taking action $( A_t )$,

- $( T )$ represents the final time step of the episode.

At the end of an episode, the agent evaluates its total reward to assess its performance. It then starts over, effectively reborn with the knowledge from its previous experiences, allowing it to make progressively better decisions. This iterative learning is evident in coding tasks. As agents become more familiar with their environment, they will develop strategies that maximize their cumulative rewards. In the context of a gaming agent, this means achieving higher scores.

Episodic tasks, therefore, are defined by their clear endpoints. We will also discuss ongoing tasks, known as continuing tasks, where there is no end. An example would be an algorithm that continuously buys and sells stocks based on market conditions, best modeled as a continuing task where the agent operates indefinitely. These agents must learn to optimize their actions continuously while interacting with their environment.

For a continuing task within reinforcement learning, the interaction sequence is unbounded and can be represented as follows:

$$ S_0, A_0, R_1, S_1, A_1, \ldots $$

where:

- $( S_t )$ denotes the state at time step $( t )$,

- $( A_t )$ denotes the action taken at time step $( t )$,

- $( R_{t+1} )$ denotes the reward received after taking action $( A_t )$,

- and the sequence continues indefinitely without a predefined ending point.

The strategies for these tasks are more complex and will be introduced later in this blog. Now, let’s dive deeper into the concept of rewards in these settings.

The Reward Hypothesis

We’ve talked about the wide-ranging uses of Reinforcement Learning, each defined by its unique agent and environment, where every agent is driven by a goal. These goals are as varied as teaching a car to navigate autonomously or training an agent to excel at Atari games. It’s fascinating that such disparate objectives can all be approached using the same underlying principles.

Up to this point, we’ve examined the concept of reward through a simple analogy: navigating a maze in a video game. In this scenario, the layout of the maze represents the state, your decisions on which turns to take are the actions, and the reward is the score or feedback you receive from the game, such as points or advancing to the next level. Just like a reinforcement learning agent, you aim to maximize this reward by learning from each interaction, which reflects the process of trial and error and gradual improvement similar to training within a Reinforcement Learning framework.

However, the Reinforcement Learning Framework generalizes this to have all agents define their objectives in terms of maximizing expected cumulative rewards. But what does ‘reward’ signify for a robot learning to walk? Could the environment act as a coach, giving feedback on the robot’s technique, rewarding good form? Yet, the reward in this context might seem subjective and unscientific. What criteria determine a ‘good’ walk versus a ‘bad’ one, and how do we quantify this in our models?

To address these concerns, we must understand that the term ‘reward’ and the concept of Reinforcement Learning are borrowed from behavioral science. It signifies a stimulus given right after a behavior to increase the likelihood of that behavior’s future occurrence.

The fact that Reinforcement Learning shares its name with a behavioral science term is deliberate, underscoring the foundational hypothesis in Reinforcement Learning:

We can always express an agent’s goal in terms of maximizing expected cumulative rewards. This is known as the “Reward Hypothesis.”

If the application of this hypothesis to complex or abstract tasks feels strange or challenging, you’re not alone.I’ll aim to further clarify and justify this fundamental concept.